The hardware and bandwidth for this mirror is donated by METANET, the Webhosting and Full Service-Cloud Provider.

If you wish to report a bug, or if you are interested in having us mirror your free-software or open-source project, please feel free to contact us at mirror[@]metanet.ch.

Using

motoRneuron for motor unit synchronization

The purpose of this document is to get you started using the

motoRneuron package for analyzing motor unit data, even if

you’ve never used R before! So we will show you how to install the

toolbox through CRAN, access the functions, help files, and sample motor

unit data. Next, we will provide code to get typical time series data

into a workable format for our functions. Then we will go step-by-step

through some analyses with this sample data to demonstrate its

applicability.

Time-domain synchronization

It’s assumed that if you’re reading this, you have at least a grasp

of what motor unit synchronization means and what you hope to get out of

this package. Briefly, time-domain synchronization, in the neuromuscular

context we are presenting it, is the tendency of separate motor units

(i.e. motor neurons and their associated muscle fibers) to discharge

near-simultaneously (within 1 - 5 ms of each other) more often than

would be expected by chance. It is often interpreted as an indicator of

functional connectivity between motor neurons through common excitatory

post-synaptic potentials. This is quanitified by a cross correlation

analyses, which is essentially the core of this package. A peak in the

resulting cross correlation histogram represents a higher probability of

discharges at that latency. Indices that quantify the magnitude of the

peak are the primary outputs for the package.

Functions

recurrence_intervals() correlates the discharge times

of one motor unit against those of another motor unit.bin() creates a cross correlation histogram from the

recurrence intervals.plot_bins() plots the cross correlation histogram with

ggplot2.mu_synch() is an all-in-one function that automatically

performs the cross correlation process from steps 1 and 2 then assesses

the histogram for peaks using 3 optional methods (listed in 4). Six

commonly used synchronization indices are returned:

- Common Input Strength (CIS)

- k’

- k’-1

- E

- S

- Synch Index (SI)

- 3 methods of peak determination are available in

mu_synch() and as individual functions:

- Visual method -

visual_mu_synch()

- Cumulative Sum (Cumsum) method -

cumsum_mu_synch()

- Z-score method -

zscore_mu_synch()

Package Implementation

Install the package from the Comprehensive R Archive Network or

Github and attach it to your workspace with the following functions.

install.packages("motoRneuron")

install.pacakges("devtools")

devtools::install_github("tweedell/motoRneuron")

library(motoRneuron)

library(ggplot2)

View the package or any of the function help files by using ‘?’.

Data: motor_unit_data

Let’s load the sample motor unit data frame from the package into the

working environment and look at it before we perform any analyses with

it. The data is 30 seconds of 2 concurrently active motor units

discharging at semi-regular intervals. It was sampled at 1000 Hz.

motor_unit_data <- motoRneuron::motor_unit_data

head(motor_unit_data)

#> Time motor_unit_1 motor_unit_2

#> 1 0.000 0 0

#> 2 0.001 0 0

#> 3 0.002 0 0

#> 4 0.003 0 0

#> 5 0.004 0 0

#> 6 0.005 0 0

You’ll see our first column is Time in seconds. The other columns

present the activation of “motor unit 1” and “motor unit 2” as a series

of binary values. A value of “1” indicates activation of the motor unit

at a specific time point, and a value of “0” indicates no activation.

Synchronization functions require actual discharge times as inputs… so

how is that obtained? We’ll help you out. We included this step because

this is a commonly used format for time series data like motor unit

discharges. To get the data in a usable form for our functions, we will

have to subset out only the time points for which each motor unit has a

value of 1.

motor_unit_1 <- data.frame(Time = motor_unit_data[["Time"]], MotorUnit1 = motor_unit_data[[2]])

motor_unit_1 <- subset(motor_unit_1, MotorUnit1 ==1)

motor_unit_1 <- as.vector(motor_unit_1$Time)

motor_unit_2 <- data.frame(Time = motor_unit_data[["Time"]], MotorUnit2 = motor_unit_data[[3]])

motor_unit_2 <- subset(motor_unit_2, MotorUnit2 ==1)

motor_unit_2 <- as.vector(motor_unit_2$Time)

You’ll see the individual motor unit data is now in vector format

containing only the time points of discharge for each motor unit.

head(motor_unit_1)

#> [1] 0.035 0.115 0.183 0.250 0.306 0.377

head(motor_unit_2)

#> [1] 0.100 0.205 0.298 0.377 0.471 0.577

So we’ve got our data in a format that our motoRneuron

functions will take.

Calculating

recurrence_intervals()

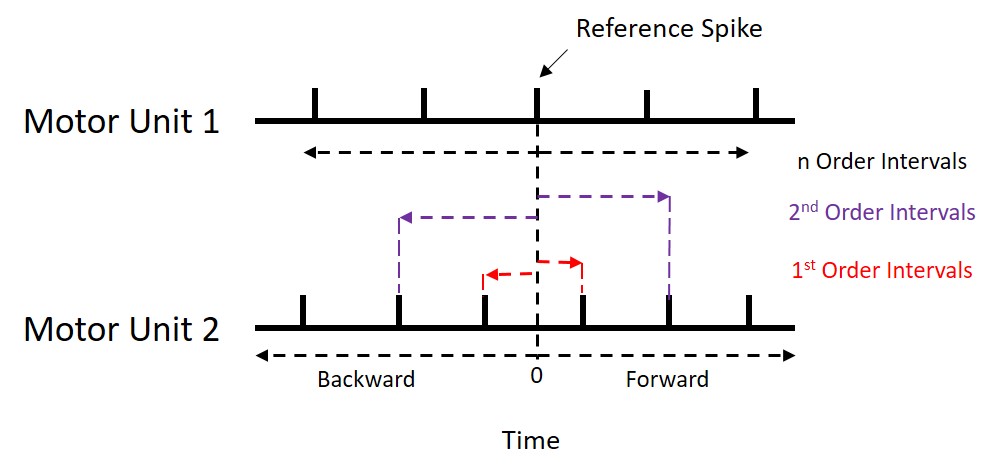

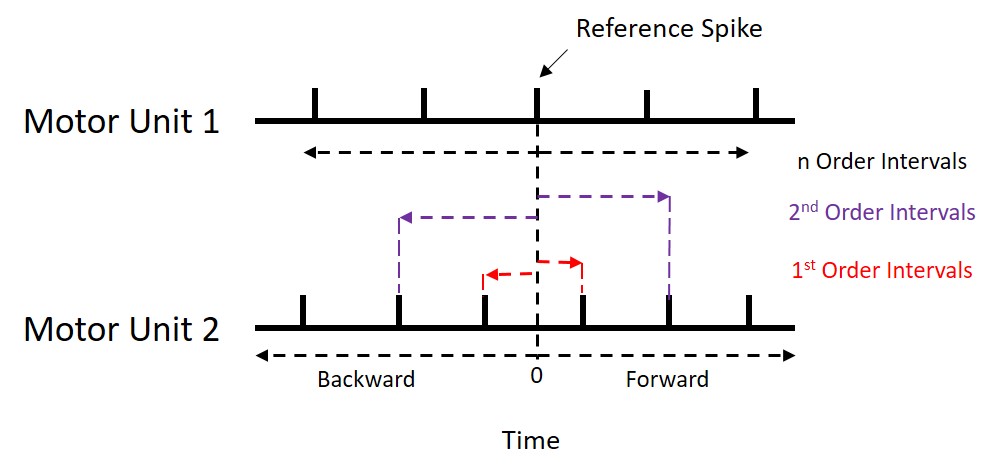

recurrence_intervals() calculates the recurrence

intervals based on how many recurrence interval orders is

specified (see image below). Specifically, they are calculated as the

timing difference between a discharge event in one (reference) motor

unit and the nearest forward and nearest backward discharge events in

another (event) motor unit. The motor unit used as the reference unit is

the unit with fewer discharges. Order refers to how many

discharges before and after we are including in our calculations.

Default settings are for first order recurrence intervals as previous

research has shown that false peaks are likely to appear with higher

orders.

The function takes the vector arguments motor_unit_1 and motor_unit_2

containing activation times, along with an integer indicating the order.

The code below calculates the time differences between the reference

activation and the first and second forward and backward discharges from

the event motor unit.

recur <- recurrence_intervals(motor_unit_1, motor_unit_2, order = 2)

names(recur)

#> [1] "Reference_Unit" "Number_of_Reference_Discharges"

#> [3] "Reference_ISI" "Mean_Reference_ISI"

#> [5] "Event_Unit" "Number_of_Event_Discharges"

#> [7] "Event_ISI" "Mean_Event_ISI"

#> [9] "Duration" "1"

#> [11] "2"

As you can see, various descriptors of the motor units are returned

as a list. For example, the mean inter-spike interval (ISI) for the

reference motor unit and the number of times the event motor unit

discharged are returned. At the end are vectors containing all the

recurrence intervals. In our example, with a recurrence interval order

of 2, the vectors produced are denoted “1” and “2”. The first pair of

numbers in vector [1] describes the recurrence interval time between the

first reference activation and the first order activation of the event

motor unit. The second pair of numbers indicates the recurrence interval

between the second reference activation and the corresponding first

order discharges from the event motor unit, and so on. For vector [2],

pairs of numbers describes the recurrence interval between the reference

discharge and the second order discharges from the event motor unit.

recur$'Reference_Unit'

#> [1] "motor_unit_2"

recur$Mean_Reference_ISI

#> [1] 0.098

recur$Number_of_Event_Discharges

#> [1] 443

head(recur$'1')

#> [1] -0.065 0.015 -0.022 0.045 -0.048 0.008

For demonstration purposes, we will only be using the first order

intervals.

Discretize recurrence

intervals with bin()

Only 2 arguments are needed for bin(); a vector

containing the recurrence intervals we just calculated and a numeric

indicating the bin size or width. Using unlist() will take

our intervals from our list format and convert them into a vector

format.

recur <- unlist(recur$`1`)

binned_data <- bin(recur, binwidth = 0.001)

A simple data frame is returned. Bin tells us how far

before or after the discharge of our reference motor unit that the other

motor unit discharged. Bin “0.000” represents the two motor units firing

at the exact same time. Freq is the frequency of that

interval occurring in the trial. Below we parse out from the data frame

only the bins representing +/- 0.015 s around the reference motor unit

discharge.

subset(binned_data, Bin >= -0.015 & Bin <= 0.015)

#> Bin Freq

#> 87 -0.015 4

#> 88 -0.014 7

#> 89 -0.013 12

#> 90 -0.012 5

#> 91 -0.011 3

#> 92 -0.010 4

#> 93 -0.009 5

#> 94 -0.008 12

#> 95 -0.007 14

#> 96 -0.006 5

#> 97 -0.005 10

#> 98 -0.004 10

#> 99 -0.003 2

#> 100 -0.002 13

#> 101 -0.001 3

#> 102 0.000 21

#> 103 0.001 13

#> 104 0.002 1

#> 105 0.003 5

#> 106 0.004 4

#> 107 0.005 6

#> 108 0.006 4

#> 109 0.007 5

#> 110 0.008 7

#> 111 0.009 4

#> 112 0.010 4

#> 113 0.011 0

#> 114 0.012 9

#> 115 0.013 2

#> 116 0.014 4

#> 117 0.015 4

Visualization of

histogram with plot_bins()

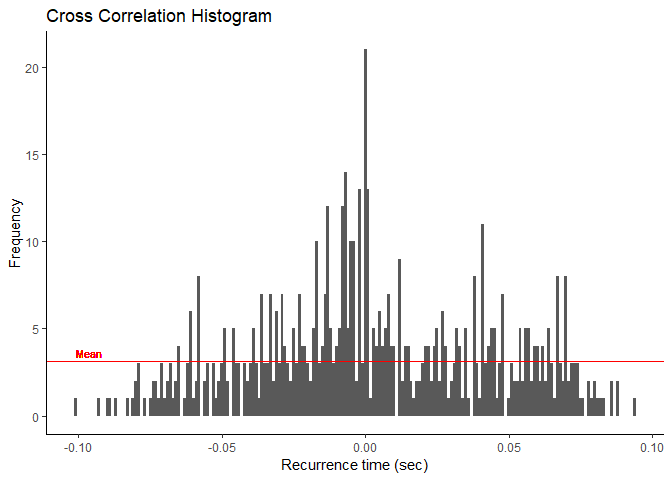

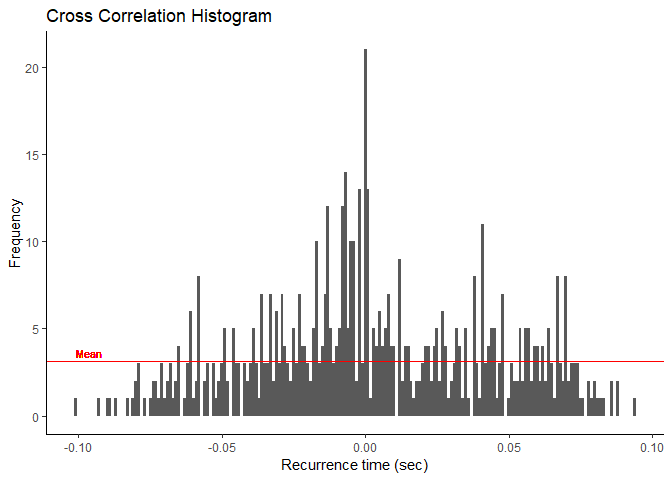

plot_bins() leverages ggplot2 to graph the binned

recurrence intervals as a histogram. Mean bin size or average frequency

of the bins is indicated as a red line on the graph.

From

the graph, we can see that there are higher frequencies the nearer to

“0.000” we get. This may indicate that there is a more than likely

chance that these two motor units are functionally connected somehow. If

there is a peak in this histogram, then our synchronization functions

will determine where it is and calculate the various indices from

it.

From

the graph, we can see that there are higher frequencies the nearer to

“0.000” we get. This may indicate that there is a more than likely

chance that these two motor units are functionally connected somehow. If

there is a peak in this histogram, then our synchronization functions

will determine where it is and calculate the various indices from

it.

Synchronization functions

mu_synch() is the all-in-one function that calls both

recurrence_intervals() and bin() to perform

the initial analysis. It then uses the user-chosen methods for

determining if and where there is a peak. More specifically, it uses

these methods to find the upper and lower boundaries of a peak if there

is one. “Visual”, “Cumsum”, and “Zscore” methods are described below and

are available for peak determination. Alternatively, each method can be

called individually using their own functions.

synch_data <- mu_synch(motor_unit_1, motor_unit_2, method = c("Visual", "Cumsum", "Zscore"), order = 1, binwidth = 0.001, plot = F)

- Motor unit vectors, “order”, and “binwidth” are the same arguments

used for

recurrence_intervals() and

bin().

- “method” is a vector of character strings representing which methods

you want to call for peak boundary determination. Default is just

“Visual”.

mu_synch() calls each specified method by their

individual functions (described later).

- “plot” is a TRUE/FALSE logical on whether to output the histogram

from

plot_bins(). Default is FALSE.

A list is returned including the motor unit characteristic data and

the 6 synchronization indices (described below) for each of the methods

chosen.

## [1] "Data" "Visual Indices" "Zscore Indices" "Cumsum Indices"

synch_data$`Visual Indices`

## $`CIS`

## [1] 2.163168

##

## $kprime

## [1] 3.79096

##

## $kminus1

## [1] 2.79096

##

## $E

## [1] 0.2110322

##

## $S

## [1] 0.08638251

##

## $SI

## [1] 0.2117218

##

## $Peak.duration

## [1] 0.01

##

## $Peak.center

## [1] 0

synch_data$`Zscore Indices`

#> $CIS

#> [1] 1.714933

#>

#> $kprime

#> [1] 4.284502

#>

#> $kminus1

#> [1] 3.284502

#>

#> $E

#> [1] 0.1673037

#>

#> $S

#> [1] 0.06848299

#>

#> $SI

#> [1] 0.1678505

#>

#> $Peak.duration

#> [1] NA

#>

#> $Peak.center

#> [1] NA

synch_data$`Cumsum Indices`

#> $CIS

#> [1] 2.163168

#>

#> $kprime

#> [1] 3.79096

#>

#> $kminus1

#> [1] 2.79096

#>

#> $E

#> [1] 0.2110322

#>

#> $S

#> [1] 0.08638251

#>

#> $SI

#> [1] 0.2117218

#>

#> $Peak.duration

#> [1] 0.01

#>

#> $Peak.center

#> [1] 0

- Common Input Strength (CIS) = extra counts in peak / duration of

time both motor units are active (s)

- k’ = total counts in peak / expected counts in peak

- k’-1 = extra counts in peak / expected counts in peak

- E = extra counts in peak / number of reference discharges

- S = extra counts in peak / (number of reference discharges + number

of event discharges))

- Synch Index (SI) = (extra counts in peak / (total counts in peak /

2))

Expected counts are the number of counts within the peak boundaries

that we would expect to have if the two motor units were independent.

This is usually calculated as the mean bin count of the baseline portion

of the histogram (<= -0.06 s and >= 0.06 s). This is explained

more in depth in the determination methods sections.

Peak location is also returned with the Synchronization Indices:

- Peak center - Describes the location of the middle of the peak and

is calculated as the median between the upper and lower boundaries.

- Peak Duration - Describes the broadness of the peak and is

calculated as the range for the upper and lower boundaries.

Visual Determination

Visual determination of peaks in a cross correlation histogram takes

a more subjective approach than other automated detection algorithms.

Investigators are usually asked where they see peaks, but as bin count

or bin frequency can vary greatly, discerning areas of greater frequncy

can be difficult for the human eye. To make it easier, the mean baseline

bin frequency (considered the mean frequncy of bins >= -0.06 s and

<= 0.06 s) is subtracted from each bin. Then the cumulative sum is

taken from these normlized bins. This method allows for normally

difficult to see increases in frequency (or peaks) to show up as

deflections in the graph. The boundaries of these deflections are the

boundaries of the peak. When called, this function automatically

configures the normalized cumulative sum then leverages the dygraphs

package to interactively display it for the user to view and determine

peak boundaries.

In the graph above you see the x-axis is just like the bins of the

cross correlation histogram, representing the time difference between

firings of the motor units. The y-axis notes the normalized cumulative

sum values for each bin. The mouse can be used to drag a vertical cursor

along the graph. This will display x and y values.

When the function is called, the user is prompted in the console to

indicate whether they actually see a deflection in the graph near time

“0.00” that may indicate a peak (y/n).

Is there a discernable change in slope or deflection near time 0 (y/n)?

- If no, default bins of +/- 0.005 s are chosen and fed into the

calculations.

- If yes, the user is prompted one at a time to input the left and

right boundaries (time points in seconds) of a peak seen as a dramatic

slope increase in the cumulative sum graph around 0. These peak boundary

bins are then fed into the calculations.

Enter the time (in sec) of the start of slope change (left or lower boundary of peak) of the graph:

Enter the time (in sec) of the end of slope change (right or upper boundary of peak) of the graph:

The synchronization function for visual determination is below. A

list similar to mu_synch() is returned.

visual_mu_synch(motor_unit_1, motor_unit_2, order = 1, binwidth = 0.001, get_data = T, plot = F)

Cumsum Determination

The cumulative sum method is an automated method that does not

require input by the user. Peak boundaries are determined as the bins

associated with 10% and 90% of the range (maximum minus minimum) of the

cumulative sum. The peak is considered significant if its mean bin count

exceeds the sum of the mean and 1.96 * standard deviation of the

baseline bins (<= -0.06 s and >= 0.06 s). If no significant peak

is detected, a default +/- 0.005 s peak duration is used.

cumsum_mu_synch(motor_unit_1, motor_unit_2, order = 1, binwidth = 0.001, get_data = T, plot = F)

Z-score Determination

Another automated method for peak determination is the z-score

method, which relies on the assumption that if two motor units are

independent (i.e. no synchronization) then the cross correlation between

them is random and the histogram would appear flat. So first, a random

uniform distribution is used to produce a flat histogram and calculate a

mean + 1.96 * standard deviation threshold for the experimental cross

correlation histogram. Any bins in the experimental histogram within +/-

0.01 s of 0.000 that crosses the threshold are considered to be

significantly greater than expected due to chance and subsequently used

for analysis. If no peaks are detected, synchronization indices of 0 are

returned. Because the z-score method tests each bin individually,

peak bins are not necessarily adjacent. Therefore, peak duration

and peak center are returned as NA.

zscore_mu_synch(motor_unit_1, motor_unit_2, order = 1, binwidth = 0.001, get_data = T, plot = F)

These binaries (installable software) and packages are in development.

They may not be fully stable and should be used with caution. We make no claims about them.

From

the graph, we can see that there are higher frequencies the nearer to

“0.000” we get. This may indicate that there is a more than likely

chance that these two motor units are functionally connected somehow. If

there is a peak in this histogram, then our synchronization functions

will determine where it is and calculate the various indices from

it.

From

the graph, we can see that there are higher frequencies the nearer to

“0.000” we get. This may indicate that there is a more than likely

chance that these two motor units are functionally connected somehow. If

there is a peak in this histogram, then our synchronization functions

will determine where it is and calculate the various indices from

it.